Lavi Pal Singh & Amit Chopra

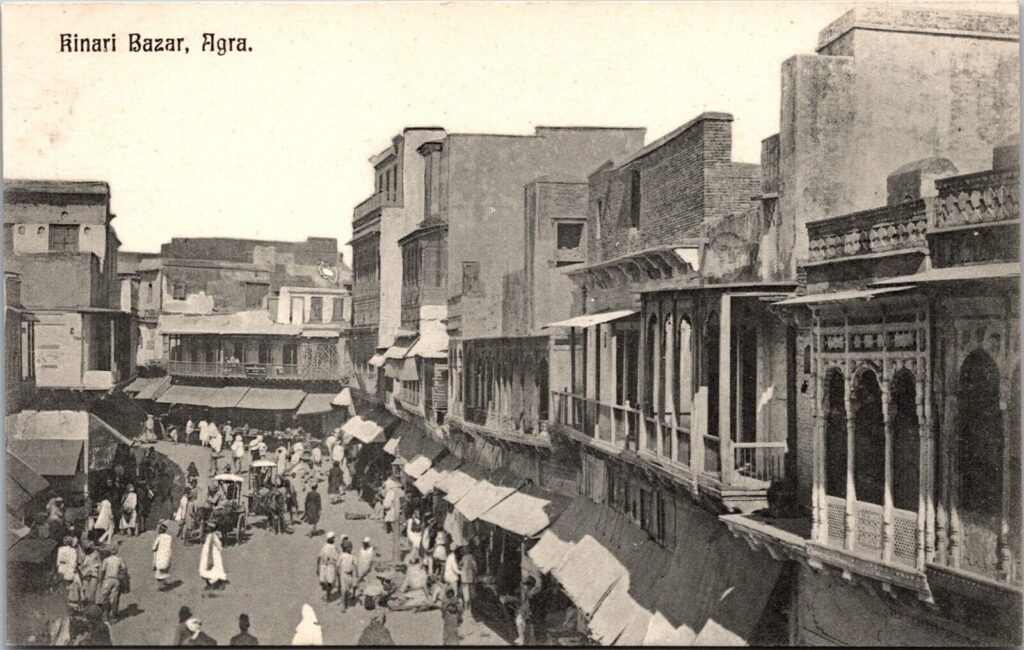

Agra, synonymous with the Taj Mahal, a testament to enduring love, has transcended its historical association to emerge as a city with a distinct identity beyond the Taj’s shadow.

Tracing its roots back to the Hindu epic Mahabharata, Agra was referred to as ‘Agraban,’ where ‘ban’ denoted “forest” in Sanskrit, portraying its origins as an arid wooded area. Legend attributes the city’s establishment to Raja Badal Singh around 1475 A.D. However, Agra gained prominence when Sikandar Lodi shifted the capital from Delhi in 1506, marking a turning point in its history.

The ascension of the Mughal Empire commenced after Babur’s victory over Ibrahim Lodi in the battle of Panipat in 1526, heralding the first Mughal ruler’s reign over Agra—Humayun, his successor. Agra flourished during the illustrious rule of Akbar, Jehangir, and Shah Jahan between the mid-16th and 17th centuries, marking a golden era in its history. However, the decline of Mughal rule ensued when Shah Jahan’s son, Aurangzeb, shifted to Aurangabad.

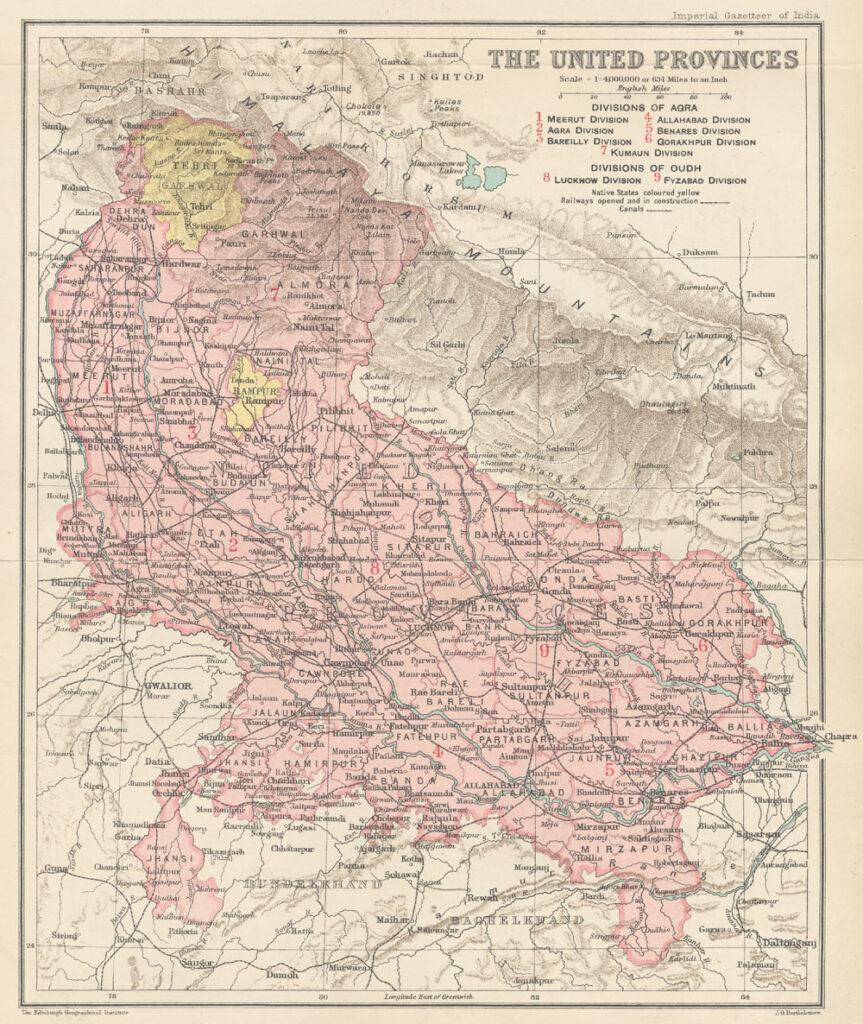

By 1803, the British East India Company assumed control, eventually establishing Agra as a Presidency in 1835 under a Governor’s administration. Following the upheaval of the 1857 revolt, British Crown rule was established, propelling Agra’s evolution into an industrial town.

The Humble Shoe Beginnings from Royal Shoes

– A Bhisti, Hing (Asafoetida), Mashq & the Akbar Army

oh! For the love of food.

The history of the shoemakers of Agra is indeed an interesting one. After 1526 – when emperor Babur occupied Agra – the city slowly and steadily became the Mughal capital for generations. Agra was one of the important centers of trade and commerce. It’s no surprise that the Mughals also influenced Agra’s cuisine. Mughlai food originally invented by fusion of existing Persian and Indian cuisines – creamy, richly flavored curries and long heritage of cuisines with an abundance of spices, dried fruits, and roasted nuts. One of the ingredients ‘Hing’ (Asafoetida) sourced from Afghanistan and Iran, came packed in leather containers called Mashq, brought on camel caravans and sold in Hing market. The discarded leather bags, left behind were used sustainably by the enterprising local craftsmen and artisans of Agra for making footwear. A natural and sustainable upcycling strange relationship between spices and shoes.

And a Savior…

In a remarkable turn of events that reshaped the narrative of Agra’s history, a water carrier known as a Bhisti emerged as a pivotal figure, altering the course of the city’s fate forever.

The saga began with a daring act of heroism when this unnamed Bhisti inflated his trusty leather goatskin satchel to save the life of none other than Humayun, the revered second Mughal emperor, from a perilous drowning in the sacred waters of the river. Crafting an improvised float from his Mashq, the Bhisti orchestrated Humayun’s safe passage across the river, a selfless act that would alter the course of both their lives.

Grateful for his miraculous rescue, Humayun, in an unprecedented gesture, bestowed upon the humble water carrier the throne of Agra for a single day. In that fleeting but impactful reign, the Bhisti showcased extraordinary vision and ingenuity. Dividing his Mashq into smaller fragments, the Bhisti transformed them into tokens of wealth by adorning them with gilded inscriptions of his own name and the date of his coronation. These ingeniously crafted pieces served as an unconventional form of currency, circulating and embedding his legacy within the economic fabric of Agra.

However, his ambitions transcended personal gain. The Bhisti, in an act of unprecedented generosity, extended an invitation to leatherworkers far and wide to partake in his newfound fortune. This inclusive act laid the foundation for Agra’s flourishing low-caste community and became the bedrock of the city’s illustrious leather industry.

The Royal Patronage

During Emperor Akbar’s reign, Agra’s leather industry experienced a transformative surge, catalyzed by a groundbreaking decree. Akbar, recognizing the necessity for his soldiers to be equipped with footwear, mandated the provision of shoes for his army, marking a departure from the Mughal tradition of barefoot combat. This directive sparked a flurry of activity, summoning shoemakers from across the empire to produce thousands of pairs annually.

Crafted with meticulous detail, shoes were embellished with opulent elements—velvet, silk cloth, and ornate embroidery, sometimes adorned with threads of gold and silver. These opulent shoes, known as “Salem Shahis,” were reserved for the Royals and Elite, a symbol of prestige and luxury. Simultaneously, footwear tailored for the Mughal Army took shape, while designs for the common populace reflected their social status, creating a diverse array of styles and craftsmanship.

This pivotal moment laid the cornerstone for what would evolve into the renowned “AGRA LEATHER FOOTWEAR” industry.Today, the heartbeat of this legacy thrives within the vibrant hub known as ‘Hing Ki Mandi.’ Surrounding areas such as Sadar Bhatti, Nai Ki Mandi, Tajganj, Bodla, Jagdishpura, Raja Mandi, Shahganj, Nanuhai, Sanjay Place, Loha Mandi, Chakkipat, Mantola, among others, collectively form the expansive canvas of this market—the largest in Asia. These areas stand as a testament to the craft, drawing footwear traders and retailers from all corners of India, shaping Agra into an eminent sanctuary for the footwear industry.

The Transitions (1835-1990’s)

British Era

After the decline of Mughal Empire, the city came under the influence of Marathas before falling into the hands of the British Raj in 1803. In 1835 when the Presidency of Agra was established by the British, the city became the seat of government. The footwear industry in General and Agra shoe industry underwent a major change.

Following the 1857 Indian rebellion, English forces in Agra and Delhi spurred a demand for English-style footwear. Local artisans adapted, learning to craft these shoes, causing a shift away from traditional Zari and embroidery work. The new trend in English-style footwear took center stage, leading to a decline in the traditional craftsmanship that once defined Agra’s footwear industry.

First Shoe Factory

In 1892, Agra saw the inception of its first shoe factory, founded by Kashmiri pandit brothers Mohan Krishan Dar and Pyare Krishna Dar, known as “Dar brothers.” This establishment, named “The Stuart Boot and Equipment Factory Limited,” situated in Talganj, owed its existence to military patronage and British supervision. The factory derived its name from Stuart, a British general stationed in Agra, who facilitated securing orders from the military. Operating under Stuart’s guidance, the factory crafted shoes using wooden lasts. However, after Stuart’s retirement and faced with formidable competition from the mechanized production in Kanpur (then Cawnpore), the company encountered challenges. By 1901, amidst these difficulties, the enterprise faltered and eventually failed. Subsequently, the factory underwent a change in ownership and was rebranded as the Dayal Bagh Taj Tannery.

The beginning of Mechanisation & Growth

In 1908, Taj Tannery changed hands when a Bengali entrepreneur named Tahir Tanner acquired it and restructured its operations under the name “Boot Eachoment Factory.” Concurrently, Syed Musa Raza introduced machinery and established the Shahganj shoe factory, specializing in Western-style footwear, which proved to be a highly successful venture.

The outbreak of World War I brought about a significant upswing for the industry. The demand surged, and the disruption in imports due to political unrest amplified production, leading to a pressing need to fulfill requirements from internal sources. This surge in demand culminated in the establishment of the Dayalbagh Footwear Factory Limited in 1917, emerging as the largest manufacturing unit of that era.

The industry’s rapid growth was aided by favorable circumstances, including reduced competition from Kanpur. The Cooper Allen Company of Kanpur had shifted its production to meet military requirements, thereby lessening the competitive pressure. Additionally, imports from Germany and Japan ceased, further bolstering the domestic market and supporting the heightened production demands.

Indeed, the foundations of Agra’s robust footwear industry were further strengthened by several key contributors:

1. K.V. & Company (Khadam Ali Khan and Faiyaz Ali Khan): Recognizing the need for innovation and quality, they employed skilled artisans and sourced literature, illustrated catalogues, and machines from English manufacturers. Embracing mechanized production techniques, they focused on crafting superior, comfortable shoes.

2. Good Luck & Company (Mestri Hardeva and Sirajudin): This venture blended the art of shoe manufacturing with astute business acumen. Their specialization in crafting Western-style footwear using meticulous hand processes marked them as pioneers in the field.

3. Other Prominent Entities: Various factories like Darbar Shoe Factory, China Footwear Factory, Men’s Footwear Factory, Senior Shoe Factory, Amdon Shoe Factory, Alexandar Shoe Factory, Poland Shoe Factory, Maharaja Shoe Factory, Kohnur Shoe Factory, Araq Shoe Factory, Burma Shoe Factory, and others played significant roles in shaping Agra’s footwear industry landscape.

Each of these establishments contributed uniquely, either by adopting modern manufacturing techniques, specializing in specific footwear styles, or combining skilled craftsmanship with business expertise. Together, they formed the bedrock of Agra’s diverse and thriving footwear industry, solidifying its reputation for quality and innovation. Inspite of the difficulties and challenges, the industry continued to grow. While in 1914 there were only 4 factories, which increased to 20 in 1929 in addition to the increase in home-based business of Jatav Tradesman.

The fortune of industry changed further as the start of World War II led to increased military requirements which were mainly fulfilled by large manufacturing factories like Bata and Flex and leaving the local civilian demand for Agra Shoe industry. Though the Quality of footwear was still ordinary but dependable, durable, and comparatively cheap thus helping common Indians in bigger cities to shift to English style of footwear for lifestyle. A major factor which gave impetus to Indian footwear industry was that British rule brought with them English designers and enhanced the skillset of the native artisans considerably.

The setting up of Agra Market & Trading System:

In the 1930s, Khadam Ali Khan spearheaded the establishment of the first central shoe market, an enduring monument in Hing ki Mandi that stands as a testament to his foresight. He united shoe factories into an association, urging them to create a hub where they could set up shops and engage with cottage industry manufacturers and distant shoe merchants. This centralized meeting points revolutionized trade, offering a space for wholesale traders, shoemakers, and other merchants to converge. This development propelled Agra into a significant hub for English-style men’s shoes between the World Wars, later exporting its products to regions like Iran, Iraq, and the East Indies after India gained independence.

Initially, shoe production thrived in places like “Sadar Bhatti,” with small retail shops in Jama Masjid and bulk wholesale operations in the market. Every evening, shoes were transported in baskets to the Shoe Market, where dealers engaged in selling them to one another. By 1945, shoe production escalated to around 50,000 pairs per day. The workforce in Agra’s leather industry also burgeoned, rising from 37,000 workers in 1939 to 50,000 by 1943-44.

Post-Independence

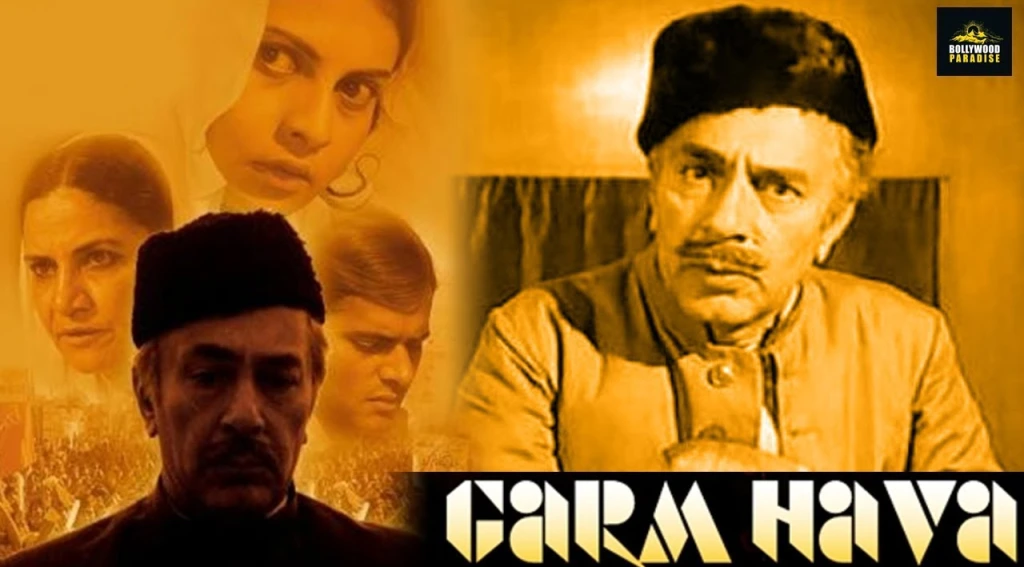

In the pre-independence period, the footwear industry was predominantly manned by Muslims. However, the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 brought about significant migration waves, reshaping the industrial landscape permanently. The migrants moving from Pakistan to India were largely Hindu-Punjabis, while those heading to Pakistan were primarily Muslim, many of whom were involved in shoe making and trade. This demographic shift had a profound impact on the industry.

The era’s sentiments and changes are depicted in Bollywood movie “Garam Hawa.” The aftermath of partition led to the closure of several renowned establishments, severely impacting production in the footwear industry. This shift in population and workforce altered the fabric of the industry, marking a poignant change that echoed across various sectors after India’s partition.

In the aftermath of partition, Agra’s regional economy, including the shoe industry, faced a decline as affluent Muslims departed for Pakistan. However, the arrival of migrant Punjabis in North India, including Agra, marked a turning point. They recognized the skilled craftsmanship of Jatavs and Muslim shoemakers and identified untapped potential due to limited market connections and underutilized opportunities for expanding the footwear business. For the Hindu-Punjabis, trading in leather was unrestricted, leading them to venture into Agra’s footwear trading upon migration. Initially, they acted as commissioning agents for shoemakers. Yet, they soon realized that purchasing footwear and selling it beyond Agra’s traditional markets was more profitable.

However, the Government’s Industrial Policy of 1956 restricted the leather industry exclusively to the small-scale sector, driven by social concerns. This policy had significant implications for the industry’s structure and operations, impacting its growth and dynamics within Agra’s economic landscape.

1970’s – Revival of a Potential Industry

The Indian Government, through its five-year plans and committees, orchestrated strategic policies to bolster the Leather and Leather Products industry, ensuring self-sufficiency and future growth:

– The Seetharamiah Committee in 1972 advocated banning raw hide and skin exports, imposing quota restrictions on semi-finished leather exports, and simultaneously increasing finished leather production capacity.

– The Kaul Committee in 1979 supported capital goods acquisition for leather production, reducing import duties on machinery for tanning, finishing, footwear, and leather goods.

– The Pande Committee in 1985 proposed steps to enhance raw material availability, modernize processes, and prioritize footwear as a crucial export item.

Agra’s footwear industry experienced significant production enhancements by embracing a new production mindset and adopting modern technology. This growth was further propelled by the trade agreement between India and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) in 1958. The treaty aimed to fortify trade relations and volume by conducting trade through barter. India purchased crude petroleum, non-ferrous metals, machinery, and fertilizers, while exporting tea, clothing, consumer electronics, spices, footwear (including leather uppers), and finished leather to the U.S.S.R. Payments were settled in Indian rupees based on Rupee-Rouble conversion. However, the distorted exchange rates between the US dollar, Indian Rupee, and Rouble posed significant challenges for Indian exporters due to the highly fluctuating currency values. To assist household artisans, small-scale and cottage units with shoe marketing and providing economical and mechanical assistance, institutions like Central Footwear Training Institute (CFTI), Uttar Pradesh Leather Development Corporation (LAMCO), SISI, Bhartiya Charm Udyog Sangh, Bharat Leather Corporation (BLC), KVIC were established. The institutions played an important role through technical support and sales of goods using their network in the country. Agra artisans followed a system of Mentor and Mentees to teach shoe craft whereby those who wished to learn shoe making skills used to go to old craftsman for training, a waning practice today.

*Note: LAMCO and BLC have been out of business for the past 5 to 7 years due to administrative reasons.

Liberalization of India’s Economy: 1990 to 2015

The early 1990s marked a pivotal phase with the economic liberalization and the Soviet Union’s decline, triggering a significant reshaping of the export trade landscape. Exporters, heavily reliant on the Soviet Union and Eastern European markets, faced a sudden loss of their primary market. They had to strategize, augment their capacities, and adapt to the more competitive Western markets while concurrently generating demand in the local market.

The Economic liberalization of 1992, alongside the Industrial Policy of the same year, aimed at accelerating export growth for leather goods, focusing on removing specific products like leather from small-scale categorization. License requirements were abolished, encouraging faster foreign collaborations and joint ventures for access to technology and raw materials. Efforts were made to modernize the industry through technological packages, educational institutions, and training centers under a comprehensive Leather development program with UNDP assistance.

This deregulation sought to enhance competitiveness by integrating the latest technology and focusing on economies of scale to meet global demand. However, it also led to challenges. Exporters, previously reliant on the secure and stable Soviet market, now faced volatility in international demand. This shift affected small-scale domestic producers adversely, causing raw material shortages, financial constraints, and machinery infrastructure needs, elevating production costs and resulting in market loss to larger players. The repercussions were swift. By 1996, a significant number of production units in Agra had shuttered, reflecting the impact of these changes on trade dynamics.

“The work which was considered to be dirty acquired great economic value”.

Agra’s industry splits into Formal and Informal Markets

In the mid-2000s, a fresh impact hit the Agra cluster due to trade liberalization, revised rules on leather imports, and increased FDI. This led to an influx of Chinese importers and manufacturers flooding the Indian shoe market with leather-like shoes at significantly lower prices. This influx exacerbated issues for the domestic sector, causing numerous shoemakers to shut down, and many traders exited the business.

However, those who persevered showcased remarkable adaptability. Some reluctantly shifted to manufacturing synthetic shoes (referred to as foam shoes by local artisans), while others turned to crafting leather shoes from discarded materials sourced from Kanpur, Kolkata, and Chennai to meet the domestic market’s affordability demands. This adaptation could be viewed as a response to market challenges, sparking some form of technological change.

To bolster exports, the UP State Industrial Development Corporation (UPSIDC) established the Export Promotion Industrial Park (EPIP) in 2002 across 100 acres in Agra’s Sikandra industrial area. Though it took until 2013 to attract export manufacturers to relocate to these units. AFMEC (Agra Footwear Manufacturers and Exporters Chamber), in conjunction with the Council for Leather Exports (CLE), aided UPSIDC in selecting the EPIP site, ensuring convenience for manufacturers, exporters, and access to skilled labor without environmental concerns.

In a bid to support small artisans and manufacturers, plans for a Leather Park were proposed in 2008, with a 100-crore fund allocation and 283-acre space designated in 2011. This Leather Park included a Shoe Mandi for exhibits, training, upliftment, trading, and sales. However, the park faced delays; the Shoe Mandi shops remain unallocated and non-operational due to legal issues within the Taj Trapezium Zone.

Furthermore, the Uttar Pradesh government selected Agra for a footwear cluster under the One District One Product (ODOP) scheme in 2018. This initiative aimed to elevate Agra’s identity globally, offering financial support for upgrading, restructuring, and adopting new technology to compete on an international level.

The Turbulent years

Navigating Industry Challenges: The Post-2016 Era

Since 2016, the industry has weathered significant upheavals, beginning with two major economic reforms in India: Demonetization in 2016 and the introduction of Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017. These were followed by the detrimental impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, deeply affecting Agra’s manufacturing and trading sectors. However, there have been positive initiatives such as the support for “Vocal for Local” and the revised definition of MSME in 2020, providing some momentum.

Despite the sector’s gradual recovery post-Covid-19 and Omicron, it faces fresh challenges, notably the increase in GST rates on footwear below INR 1000 from 5% to 12% in 2021. Additionally, there’s a push for ensuring quality standards through mandatory BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards) certification imposed on footwear products from 2023, further shaping the industry landscape.

& another Footwear and Leather Policy support…

For support industry Central Government in January 2022 announced continuation of ‘Indian Footwear and Leather Development Program (IFLDP) scheme till 2026. The Policy covering multi-aspects across

- Manufacturing – Modernization; capacity expansion; technology upgradation, Mega Leather Footwear and Accessories Cluster Development

- Sustainability – Setting up Common Effluent Treatment Plant), design and marketing of footwear.

- Marketing – Central assistance for Brand Promotion of Indian Brands in Footwear and Leather Sector

- Designing Infrastructure – Central assistance for setting up and development of Design Studios

- Training and up-Skilling – Establishment and upgradation of Institutional Facilities like FDDI

Agra’s Industry today (Facts & numbers)

Agra manufactures approximately 4.5 crore pairs of shoes annually, averaging 150,000 pairs per day. This production includes 2.2 crore pairs of chappals and sandals, employing about 4.35 lakh individuals across an estimated 30,000 units, encompassing the surrounding regions. Traditionally, Agra has specialized in catering to the domestic footwear market, with a smaller segment dedicated to exports. Presently, it stands as India’s primary hub for (leather) footwear production, contributing to 65% of the domestic market and accounting for 35% of India’s total footwear exports. More than a quarter of the city’s population is directly or indirectly involved in the footwear industry.

Agra’s footwear spectrum spans from high-quality premium leather to non-leather products. Industry associations like AFMEC, CLE, CFTI, and other exporters highlight Agra’s swift responsiveness to buyer demands regarding seasonal and fashion trends as a key strength. Different areas within the city specialize in various levels of production activities. Agra benefits from ample raw material availability and a robust network of input suppliers. The cluster-based approach has significantly contributed to the city’s growth, serving as a successful model in its development.

The footwear industrial units in the region can be broadly categorized into four major types:

1. Household Units & Household Workshops:

a. Operated mainly by family members of unit owners, utilizing traditional skills, basic tools, and minimal machinery.

b. Manpower: 3-10 employees; typically family members or hired on a contract basis.

c. Production: 24-48 pairs/day.

d. Account for 50-60% of the total footwear units.

2. Workshop Units (Karkhana):

a. Primarily serve domestic markets, with a few involved in exporting shoes or uppers through merchant exporters. Partially mechanized with limited machinery, sometimes outsourcing upper stitching to household units.

b. Manpower: 20 to 40, mainly contractual.

c. Production: 100-500 pairs/day.

d. Constitute 30-40% of the total footwear units.

3. Semi-Mechanized Units:

a. Operate with a hybrid approach, combining handmade and modern machine processes for shoe uppers and full shoes.

b. Serve both national branded players and international brands or clients for exports.

c. Manpower: 40 to 100 employees.

d. Production: 200-1000 pairs/day.

e. Contribute to 10-20% of the total footwear units.

4. Mechanized Units:

a. Utilize modern advanced machinery extensively for most shoe manufacturing operations, following assembly line production.

b. Primarily cater to prominent international premium and luxury brands.

c. Manpower: 200-500+ employees.

d. Production: 1000-3000 pairs/day.

| Year | Mechanized & Semi-Mechanized Units | Workshop Units (Karkhana/Cottage) | Household and Informal Units |

| 1970 | 10 | 50 | 3,000 |

| 1980 | 15 | 85 | 7,000 |

| 1990 | 25 | 120 | 13,000 |

| 2000 | 40 | 180 | 18,000 |

| 2010 | 60 | 3,000 | 24,000 |

| 2020 | 250 | 5,000 | 30,000 |

This table demonstrates the growth trends in the number of units categorized as Mechanized & Semi-Mechanized, Workshop Units, and Household/Informal Units across different years, showcasing a substantial rise in each category over time. Source- DIC-Agra, https://agra.nic.in/economy/

Estimates of Workers in Footwear Sector in Agra 2020

| S.No. | Types of Production Units | Employment (Direct) |

| 1 | Household units | 350,000 |

| 2 | Household workshop | 10,000 |

| 3 | Non-household workshop | 10,000 |

| 4 | Semi-mechanized workshop | 20,000 |

| 5 | Mechanised factories | 15,000 |

| 6 | Workers in ancillary units | 18,000 |

| 7 | Women job workers | 10,000 |

| 8 | Factory workers(women) | 2,000 |

| Total | 4,35,000 |

Source- DIC-Agra, https://agra.nic.in/economy/

*However different agencies have quoted different numbers of workers in footwear sector. Director of Adhar: 1-1.5 lacs; Director, Leather, SISI: 2 Lacs. CLE, Agra: 3.5- 4 Lacs

(Note: Adhar is an NGO working with Central Leather Research Institute (CLRI) on the Umbrella Project)

The Stakeholder Network

Being a mature footwear manufacturing market, Agra has a strong network of stakeholders to support footwear manufacturing community of the region.

Industry Associations

- Agra Footwear Manufacturers Exporters Chamber (AFMEC)

- Agra Juta Dastkar Federation (AJDF)

- Bhim Yuva Vyapar Mandal (BYVM)

- Agra Juta Laghu Udyog Utpadak Samiti (AJLUUS)

- Agra Shoe Manufacturers Association (ASMA)

- Boot Manufacturers Association (BMA)

Shoe production Cluster, Mohalla’s and trading zones

| Area Cluster | Name of Mohallas |

| Sadar Bhatti | Dhawlikar, Ghatia Mamu Bhanja, Mantola, Teela Nand Ram, |

| Agra Mathura Road (By-pass) | Khandari, Sheetla Road, Sikandra, Artauni, Dhanoli, |

| Hing Ki Mandi | Traders |

| Nai Ki Mandi | Chota Ghalib Pura, |

| Shahganj | Prakash Nagar, Prem Nagar, Rui ki Mandi, Barakhamba, Bhogipura, Prithvinath, |

| Agra Cantonment | Nandpura, Nai Basti, Pakki Sarai, Naripura |

| Loha Mandi | Jagdish Pura, Garhi Bhadoriya, Madiya Katra |

| Collectorate | Sunder Para, Idgah, Nagla Fakirchand |

| Talaiya | Nala Kaji Pada, Chakkipat |

| Sanjay Market | Trading Offices |

| Other Localities: Ratanpura, Tajganj; Nagla Chidda; | |

Academia

- Central Footwear Training Institute (CFTI), Agra a premium institute for footwear professional education, upskilling programs, and providing technical services to the MSME.

- Dayal Bagh Educational Institute (DEI), Government Leather Institute (GLI) are other institutions for leather and footwear learning.

Lasts Makers:

- New shoe lasts, made up of wood or PVC, are required by enterprises to cater frequent changes in shoe design.

- 7-10 PVC last manufacturers and 60-80 wooden last manufacturers.

- PVC lasts offer better quality, durable and recyclable; wooden last used for their low cost for economical shoe manufacturing.

Shoe Soles:

- 100-150 manufacturing units.

- Types of soles like TPR, PV. PU, MCR Sheet, PVC and meet 70-80% of total demand.

Machinery suppliers:

- 10-15 footwear machine manufacturers and 15-18 agents & dealers dealing in all type of Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, Indian & European machines.

Raw material & components

- Over 100 raw material manufacturers

- Most types of Upper materials – leather & synthetic and other components and Grindery material (adhesives, insole, stiffeners, eyelets, and laces) are easily available in the local wholesale markets to serve the industry network.

Regulatory Issues:

- Footwear manufacturing industry is in ‘Green’ category” and unit mandated to take ‘Consent for Operations (CFO)’ from the State Pollution Control Board (SPCB).

- Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ): an area of 10,400 km2 around the Taj Mahal. As per SC directive, footwear units under the TTZ are banned from using coal or coke in units and are mandated to switch over to natural gas.

The Trade Credit “Parchi” System:

The informal structure of Agra’s domestic supply chain operates from manufacturers to traders, wholesalers, and retailers before reaching consumers. Most transactions occur on credit, potentially causing financial strains for small artisans, manufacturers, and traders. To address this cash flow requirement and ensure credibility in commitments, Agra’s market devised an innovative method known as the “parchi” system.

When shoe transactions take place, a “parchi,” or paper slip, is provided to the shoemaker, detailing the trader’s name, the amount owed, and the due date for payment. Signed by the traders, this slip acts as a promissory note, transferable to others. The parchi helps maintain financial liquidity by ensuring traders fulfill their obligation to whoever presents the slip on the due date. In response, informal financial intermediaries known as “aadhatiyas” have emerged. They purchase parchis at a discount and encash them from traders on the due date, earning through this discount. This system facilitates liquidity for shoemakers or traders while granting traders the credit they require. In some cases, parchis even function as a form of currency when shoemakers purchase raw materials using these slips. Trusted and sanctioned within the market, the parchi has become an accessible, efficient, and trustworthy commitment within this informal financial system.

The GI – Tag

Geographical Indications (GIs) represent a form of intellectual property that indicates a product’s origin. These indications signify the reputation, quality, or distinctive attributes of a specific product owing to its geographical origin. GIs cover various categories, including agricultural, natural, or manufactured goods, with the latter requiring production within a specific geographic area. The recognition of GIs serves two key purposes: it instills trust among consumers, enabling them to identify and appreciate quality products, while simultaneously assisting producers in enhancing the marketing of their goods.

GI Origins

Geographical indications (GI) emanate from Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (or TRIPS) Agreement, which came into effect on January 1, 1995. The core objective of the TRIPS agreement was to establish standardized protection measures for Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) across member nations. This involved implementing specific general principles and mechanisms for dispute resolution among WTO Members. Article 22 of the TRIPS agreement mandated governments to offer legal avenues to owners of a Geographical Indication (GI) registered in their country, allowing them to prevent the use of marks that could mislead the public regarding the actual geographical origin of a product. This prevention extends to cases where a geographic name, while factually accurate, could create a false impression that the product originates from a different location. Additionally, this provision allows interested parties to request the refusal or invalidation of a trademark registration that incorporates a geographical indication concerning goods not originating from the indicated territory.

Geographical Indicators in INDIA & Fashion

India, as a founding member of the WTO, ratified the TRIPS Agreement in 1994, which became effective on January 1, 1995. The country introduced the Geographical Indications (Registration and Protection) Rules in 1999, enforced under the Geographical Indications (Registration and Protection) Rules, 2002. Before this enactment, there were no specific laws governing GIs in India. The GI Act played a pivotal role by:

– Governing GIs of goods nationwide, benefiting the producers.

– Safeguarding against GI misuse, protecting consumers from deception.

– Promoting India-specific goods with GI tags in the global export market.

The Act delineates key terms and interpretations, such as geographical indication goods, producers, package, registered proprietor, authorized user, among others. GI tags serve a distinct purpose from trademarks, indicating the product’s origin, belonging not to an individual or entity but to an entire region or community.

It’s important to note that GI registration is optional in India. The registration process involves two steps: initial registration of the product and its area, followed by the registration of manufacturers and users. For a product to gain popularity and recognition worldwide, it must first establish awareness within India.

Darjeeling Tea from West Bengal secured the first GI tag in India in 2004, while Pochampalli Ikat from Telangana was the inaugural handicraft textile under the fashion category. As of August 31, 2023, India has 475 products registered with GI tags, comprising 441 Indian goods and 34 international goods across categories like agriculture, handicrafts, manufacturing, foodstuff, wines, spirits, and natural goods. Among the 441 Indian GI tags, a substantial number are related to handicrafts and manufacturing processes involving textiles, embroidery, weaving, dyeing, and printing, components integral to fashion apparel. Additionally, 7 GI tags are associated with handicrafts and manufactured goods in the footwear and leather industry. A recent addition to this list was the Agra Leather Footwear, receiving its GI tag in August 2023.

- Table 1

GI Tags related to Footwear and Leather

| Geographical Indications | Good Category | State | Applicant | Year Registration |

| East India Leather | Manufactured | Tamil Nadu | The Trichy Tanners Association Society & The Dindigul Tanners Association | March 2008 |

| Leather Toys of Indore | Handicraft | Madhya Pradesh | Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) | July 2008 |

| Santiniketan Leather Goods | Handicraft | West Bengal | Santiniketani Artistic Leather Goods Manufacturer’s Welfare Association | September 2008 |

| Andhra Pradesh LeatherPuppetry | Handicraft | Andhra Pradesh | Andhra Pradesh Handicrafts Development Corporation Ltd. | September 2008 |

| Kolhapuri Chappal | Handicraft | India(Karnataka & Maharashtra) | LIDCOM & LIDKARFacilitated by Central Leather Research Institute (Council of Scientific & Industrial Research) | December 2018 |

| Chamba Chappal | Handicraft | Himachal Pradesh | Ambedkar Mission Society ChambaFacilitated byHimachal Pradesh Patent Information Centre | September 2021 |

| Agra Leather (Footwear) | Manufactured | Uttar Pradesh | Agra Footwear Manufacturers & Exporters Chamber | July 2023 |

GI – Advantage, Challenges & way forward

The essence of India embracing GI Tags lies in authenticating its rich heritage, particularly in handicrafts, agriculture, and manufacturing, collectively owned by producers within a region. These tags offer recognition to rural areas, artisans, and generations of craft legacy. They serve as a form of protection for those unable to invest in branding, asserting their original skills developed over centuries. GI tags establish brand equity, vouching for the authenticity of the product’s origin.

While GI tags don’t guarantee export success, they grant assurance to both large and small-scale producers, including less-recognized export contributors, expanding business opportunities beyond borders. However, post-registration, efforts to amplify the product’s aura have been limited. Producers lack resources for marketing, product enhancement, and brand building.

Government initiatives and a clear policy framework are essential to raise awareness among GI product manufacturers. Beyond being a brand-building tool, government support through funding, tax benefits, incentives, and education is vital to leverage GI tags. Lack of awareness hinders the potential of GI tags in popularizing indigenous, high-quality products globally, improving livelihoods and encouraging investments in rural communities.

Maintenance of quality standards is often overlooked. Contrastingly, the zeal with which Champagne GI is protected and promoted emphasizes excellence, forming the cornerstone of its designation, not just a geographical indication. In India, despite numerous GI tags, opportunities to enhance branding and commercial value remain largely untapped, spanning various handicrafts like textiles, garments, footwear, and leather products.

A classic case like Banarasi Sarees and Brocades highlights the gap between GI tag issuance and tangible benefits. The weavers struggle as the motifs and designs are replicated using inferior materials at higher prices. Lack of a unified representative body exacerbates their challenges, warranting legal aid and representation.

The Indian Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999 strives to preserve India’s cultural wealth but faces implementation gaps. Unauthorized use of GI tags persists without concrete prevention measures. These tags cater to manufacturers lacking the resources for high-cost branding, necessitating a multilateral system for protection. Successful GI stories remain scarce due to insufficient marketing, consumer awareness, and legal recourse.

What Next for Agra Leather Footwear!

In the ongoing pursuit of leveraging Geographical Indication (GI) tags for Agra’s Leather Shoe Manufacturing, the Agra Footwear Manufacturers & Exporters Chamber (AFMEC) has made strides to establish Agra Footwear on the GI map. However, this achievement marks just the beginning of a larger endeavor.

Looking ahead, AFMEC faces the challenge of effectively utilizing the GI tag to gain commercial advantage in both global and local markets. Balancing the interests of local artisans with export aspirations will be crucial in reasserting Agra’s heritage and global standing in the realm of Leather Footwear.

The critical aspect lies in maintaining stringent quality control standards throughout the supply chain to ensure the final product aligns with the defined specifications. Equally essential is providing workshops, skill development programs, and awareness initiatives for artisans to refine their craftsmanship, preserving this integral part of Indian history. Safeguarding the credibility of the 400,000+ Agra artisan community is paramount. Regulating markets to eliminate counterfeit and substandard products is vital in upholding the authenticity of Agra’s footwear.

The success stories of iconic products like French Champagne, Columbian coffee, Havana Cigars, and Tennessee whiskey demonstrate the significance of organized marketing strategies in building exclusivity and premium value. Beyond the GI tag, comprehensive policy reforms and robust marketing endeavors are imperative to establish a brand identity, ensure recall value, and directly engage consumers while consistently delivering impeccable quality and craftsmanship.

The question lingers: Could Agra Leather Footwear mirror the Champagne moment for India’s GI team and the Footwear Industry?

The answer rests in the collective efforts to infuse innovation, quality, and strategic marketing to elevate Agra’s footwear to a global pedestal, setting a new standard in the world of GI-tagged products.